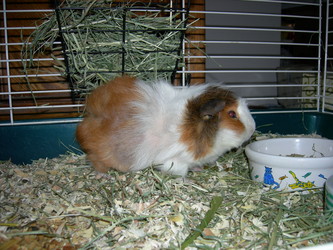

Cavia porcellus. Author's pet guinea pigs. Left: Shadow. Right: Chiquita. Both images © 2008

Introduction

Humans have kept and used the domestic guinea pig for thousands of years. In Western societies, these social rodents are kept as pets, bred for show, and used in scientific research. In some societies, guinea pigs are a source of food, and the Andean culture uses them in religious ceremonies and traditional medicine.

Classification

Guinea pigs belong to the family Caviidae, which is a family of South American rodents. This group sometimes is referred to as Caviomorpha, or guinea-pig-like rodents (D'Erchia et al. 1996; Wagner 1976). Rodentia contains three sub-orders: Sciuromorpha, Myomorpha, and Hystricomorpha. Caviidae usually is placed within Hystricomorpha (Graur, Hide and Li 1991; D'Erchia et al. 1996). However, in the early 1990s a debate arose over whether or not guinea pigs and Caviomorpha should be classified in Rodentia.

Graur, Hide, and Li (1991) performed phylogenetic analyses of amino acid sequences of various taxa. Their interpretation of the results suggested that Caviomorpha should be considered a separate order from Rodentia. In 1996, D'Erchia et al. analyzed the complete guinea pig mitochondrial genome and concluded that guinea pigs should be classed in an order distinct from Rodentia. In other words, Rodentia is paraphyletic. However, Luckett and Hartenberger (1993), Sullivan and Swofford (1997), and others argued for keeping Caviomorpha in Rodentia based on morphological data and criticisms of the methods used by Graur, Hide, and Li (1991), and D'Erchia et al. (1996). Currently, some data supports the paraphyletic side of the debate, but guinea pigs are generally considered part of Rodentia.

Evolution and Domestication

Ancestral caviomorphs probably descended from paramyid rodents found in North America, Eurasia, and North Africa. Members of Caviidae first appeared during the Late Miocene period, 26 to seven million years ago, and the family diversified in that period as well (Alderton 1999; Wagner 1976).

The domestic guinea pig originates in the mountains and grasslands of the Altiplano region in South America. Domestication may have begun around 5,000 BCE (CFHS; Morales, 1995). Nowak (1999) asserts that Cavia porcellus probably derived from C. aparea, C. tschudii, or C. fulgida, and is now distinct from all of these. According to Alderton (1999), it was once thought that C. aparea (the Brazilian cavy) was the wild ancestor, but it is now thought that C. tschudii (the Peruvian cavy) is probably the ancestral form.

Today, guinea pigs live all over the world. They can adapt to a wide range of altitudes, from sea level to higher than 4,000 m (NRC 1991). In South America, where people keep them for food, they are allowed to run free on the floor in kitchens or outdoors (Morales 1995). Sometimes pet guinea pigs are allowed to "free range", too, but oftentimes their caregivers will keep them in cages. Guinea pigs thrive at room temperature; colder weather can be deadly (CFHS). However, guinea pigs can be surprisingly hardy. The BBC reports that a guinea pig was abandoned outdoors in Cornwall, England, and survived there for five years.

Names

The species name porcellus means "little pig" in Latin (Wagner 1976). Although guinea pigs are not members of the pig family, they do resemble suckling pigs when they are skinned and dressed for cooking. Also, some of their vocalizations sound somewhat like pig vocalizations (Wagner 1976; Alderton 1999).

C. porcellus has several common English names, including "guinea pig", "cavy", and "cuy". The origins of "guinea pig" are not clear. The "pig" part of their name probably shares the same origins as their species name. Europeans first encountered the animals in the mid-sixteenth century, after the Spanish Conquest of South America. It is possible that guinea pigs were sold for a guinea (a type of English coin) at that time and were thus named for their price. Or, Europeans might have thought guinea pigs came from the African country Guinea, since ships carrying the animals from South America often stopped there before returning to Europe (Alderton 1999). It is also possible that "guinea" is a corruption of the name of the South American country Guiana (Morales 1995). Another common English name is "Cavy". Breeders of guinea pigs for show often refer to them by this name, which is taken from the animal's scientific name, Cavia porcellus (Wagner 1976). Cavy may also be a modified version of the South American "cuy". This name is similar to that used by several Native South American languages. "Cuy" sounds like a guinea pig vocalization (Morales 1995; Wagner 1976).

Male guinea pigs are called boars, females are referred to as sows, and young are called pups (CFHS).

Physical Characteristics

Guinea pigs measure 20 to 40 cm from head to rump; they do not have tails (Nowak 1999). Like all members of Caviidae, guinea pigs have four toes on each front paw and three toes on each hind paw (Alderton, 1999). Adult guinea pigs usually weigh 500 g to 1500 g, but the National Agrarian Research Institute of Peru has developed a "super-cuy" that weighs up to 3 kg (Nowak 1999; Economist 2004)! In general, females tend to weigh slightly less than males (CFHS).

Guinea pig incisors and molars grow continuously. They wear down from the guinea pig chewing its roughage-rich diet (CFHS; Navia and Hunt 1976).

Senses

Adult guinea pigs seem to be able to discern brightness, but not hue. Young are born with their eyes open, but studies reported by Harper (1976) suggest that their vision is poorly developed at birth. Scent plays a role in guinea pig communication, and mother guinea pigs use it to identify their young. Guinea pigs can hear sounds of up to 40,000 to 50,000 Hz, and some guinea pig vocalizations have ultrasonic components above 20,000 Hz (Harper 1976).

Coat

The wild relatives of guinea pigs have ticked grey coats similar to that of Shadow (see pictures). Breeding guinea pigs for research and show has produced many combinations of coat colour, length, and quality. Sewall Wright studied guinea pig coat type and pigmentation extensively (Festing 1976; see Wright 1935 for an example of his research). Common colours include white, brown, black and combinations thereof. Guinea pig fur may be long or short, straight, frizzy or curly, soft and silky or rough and harsh, and it may lie smoothly or in rosettes (Morales 1995; ACBA).

Behaviour

Activity

Guinea pigs are most active at dawn and dusk, but they are active throughout the day. Under conditions of constant light and temperature in the lab, they do not appear to have fixed sleeping or eating patterns (Harper 1976).

Social Behaviour

As social animals, guinea pigs will seek contact with one another and tend to associate in groups of several to several dozen if given the opportunity to do so. They investigate unfamiliar guinea pigs by nose-to-nose contact and anogenital nuzzling (Alderton 1999; Harper 1976). Guinea pigs interact and socialize with their caregivers when kept as pets (CFHS). For example, they may chirp at their caregiver to ask for food.

In groups of guinea pigs, males have a linear hierarchy. The alpha male has exclusive rights to mating with the females in his group, and will not tolerate other males attempting to mate with his females. Females are subordinate to their male, and they may have a loose social hierarchy among themselves (Harper 1976).

Locomotion

Guinea pigs are quadrupedal. They walk and run on the soles of their feet (Alderton 1999). Young guinea pigs play by "popcorning", that is, by jumping, bucking, and throwing up their heads (CFHS; Harper 1976). In response to danger or fright, guinea pigs will either freeze or run away. Groups of guinea pigs may respond by suddenly scattering in all directions (Harper 1976).

Communication

Guinea pigs communicate with one another by making sounds (CFHS; NRC 1991). They produce a variety of vocalizations that go along with certain activities. For example, a guinea pig will "chutt" when exploring, "whistle" when fed by a caregiver or when separated from a companion, and "purr" when seeking contact (Harper 1976).

Guinea pigs also use scent to communicate. Scent from adanal glands may be used to mark territory. In courtship, an unreceptive female will sometimes squirt a jet of urine at the persistent male, who then sniffs it. While the male investigates, the female escapes. Alternatively, the persistent male may squirt urine at the female, possibly in an attempt to mark her as part of his group (Harper 1976).

Feeding

Guinea pigs are herbivores (CFHS). They feed in groups with little competition for food (Harper 1976). Unlike other rodents, guinea pigs cannot manufacture vitamin C; they must consume it in their diet. Sources of dietary vitamin C include fresh vegetable matter and supplements that caregivers add to food or water (CFHS; Ediger 1976; Navia and Hunt 1976).

To extract as much nutrition as possible from their cellulose-rich diet, guinea pigs use coprophagy. They cannot digest cellulose themselves, but bacteria in their cecum can. However, once food has reached the cecum, guinea pigs cannot absorb nutrients from it. So, they pass and eat special, soft fecal pellets containing bacteria-digested cellulose (Alderton 1999; Harper 1976).

Cavia porcellus. Shadow feeding on a lettuce leaf. © 2008

Reproduction and Life Cycle

Reproductive Cycle and Mating

Sexually mature female guinea pigs go into estrus every 13 to 20 days except when pregnant. The vagina is closed by a membrane, which disappears at the beginning of estrus and re-forms at the end (Ediger 1976).

A male guinea pig courts a female by purring, swaying his hindquarters, following or circling, and licking and sniffing the female's anogenital region. The female also purrs, sways, circles and licks the male. To indicate receptivity, the female raises her hindquarters. After mating, the male guinea pig grooms his genital region and drags his hindquarters along the ground. In the female, a plug made of sperm and vaginal cells forms in the vagina, and falls out a few hours later (Harper 1976).

Pregnancy and Birth

Pregnancy lasts about 68 days. Guinea pigs give birth to, on average, two to three young per litter. Newborn pups each weigh about 85 g to 95 g at birth. After the pups are born, the mother eats the placenta and fetal membranes (Harper 1976). In order to give birth, the mother's pubic bones must separate, as the pups are large. If a female guinea pig does not breed before six months of age, her pubic bones may fuse. If this happens, it prevents her from giving birth, resulting in the death of the mother and her unborn pups (NRC 1991; Harper 1976).

Precocial Young

Guinea pig pups are precocial. They are born fully-furred, with well-developed sensory and locomotor abilities, and they can consume solid food the same day they are born (Kunkele and Trillmich 1997). Pups can be weaned after five days, but they normally nurse for three weeks or more. Milk consumption decreases as solid food consumption increases (Nowak 1999; Kunkele and Trillmich 1997; Harper 1976). The mother grooms her young very little. She does lick the anogenital region of her pups for the first two or three weeks in order to stimulate urination (Harper 1976).

Kunkele and Trillmich (1997) found that having precocial young does not significantly lower the overall biological cost of lactation for the mother, since the well-developed young have high energy needs right after birth. However, the pup's milk consumption decreases rapidly, and so daily maternal energy expenditure decreases also. This strategy may enable guinea pigs to breed throughout the year, even in times of scarce food.

Maturity and Life Span

Females reach sexual maturity at two months of age; males reach it at three months (Nowak 1999). Pet guinea pigs usually live five to seven years if given proper care (CFHS).

Uses

South American Culture

Guinea pigs have been an important part of South American culture in the Andean region (in Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia) for thousands of years. Incans used them in religious ceremonies, and they also mummified them (Alderton 1999; Morales 1995). The Spanish Conquest introduced Roman Catholicism to South America, and traditional beliefs and practices combined with the new religion. For example, people in Peru use guinea pigs in the celebration of patron saint days. Also, Andean traditional medicine uses guinea pigs for diagnosis and healing (Morales 1995).

Meat

In South America, guinea pigs are eaten on special occasions and are considered a delicacy. Today, there are commercial guinea pig farms in South America, but many Andeans still raise them in the traditional manner. The animals run loose in kitchens where they feed on kitchen vegetable scraps (Morales 1995). Guinea pigs are also a source of meat in Nigeria and other parts of Africa, as well as in the Philippines (NRC 1991).

Pets

Guinea pigs are kept as family pets and bred for showing. Cavy breeding clubs in Europe and North America, such as the American Cavy Breeders Association, set breed standards and organize shows and competitions.

Scientific Research

Guinea pigs have been used in scientific research since the mid-1800s for studying pathology, nutrition, heredity, and toxicology, and for the development of serums (Nowak 1999; NRC 1991). Various aspects of their physiology and anatomy make them ideal lab animals. For example:

- Guinea pig gestation is long enough to permit easy differentiation between stages of embryological and fetal development (Hoar 1976).

- Guinea pigs are useful for studying collagen biosynthesis, as they do not produce their own vitamin C, unlike other small lab animals such as mice, rats, and hamsters (Navia and Hunt 1976). Collagen biosynthesis requires vitamin C.

- Compared to that of other small lab animals, the guinea pig electrocardiogram waveform is more similar to the human waveform. Also, guinea pigs generally are calm animals, so it is possible to obtain continuous and stable readouts (Sisk 1976).

- Hearing studies use guinea pigs since their inner ear is readily accesible (McCormick and Nuttal 1976).

- Guinea pigs are ideal canditates for germ-free research, since their precocial young have a good chance at surviving from birth on solid food. Scientists surgically remove the pups from the pregnant guinea pig in a sterile environment, and then raise them on sterile food in a germ-free environment (Wagner and Foster 1976).

Information on the Internet

- Cuyes: Platos Peruanos al Estilo Lunahuaná Guinea pig recipes from the Ministry of Agriculture of Peru. The page is written in Spanish. Google Language Tools can give a quick translation into English.

- American Cavy Breeders Association Links to pictures of breeds that the ACBA recognizes.

- NCBI Taxonomy Browser entry for Cavia porcellus. Includes genomics information.

- Microlivestock: Little-Known Small Animals With a Promising Economic Future (NRC.) Information about raising guinea pigs for food.

- 'Popular' guinea pig feared dead. BBC news story about a guinea pig that lived in the wild for five years in Cornwall, England.

- The Canadian Federation of Humane Societies (CFHS.) Information on keeping guinea pigs as pets.

Go to quick links

Go to quick search

Go to navigation for this section of the ToL site

Go to detailed links for the ToL site

Go to quick links

Go to quick search

Go to navigation for this section of the ToL site

Go to detailed links for the ToL site