Xerini

African ground squirrels

Scott J. Steppan and Shawn M. Hamm

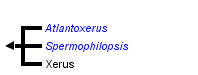

This tree diagram shows the relationships between several groups of organisms.

The root of the current tree connects the organisms featured in this tree to their containing group and the rest of the Tree of Life. The basal branching point in the tree represents the ancestor of the other groups in the tree. This ancestor diversified over time into several descendent subgroups, which are represented as internal nodes and terminal taxa to the right.

You can click on the root to travel down the Tree of Life all the way to the root of all Life, and you can click on the names of descendent subgroups to travel up the Tree of Life all the way to individual species.

For more information on ToL tree formatting, please see Interpreting the Tree or Classification. To learn more about phylogenetic trees, please visit our Phylogenetic Biology pages.

close boxIntroduction

The tribe Xerini consists of three genera and six species of terrestrial squirrels known as the African and Long-Clawed Ground Squirrels. The tribe is predominantly distributed among Africa’s arid and semi-arid regions, with one species found only in Central Asia (Northern Iran and Afghanistan). Xerini includes smaller to medium-sized squirrels, with head and body lengths of 16 to 46 cm, tail lengths ranging from 7 to 27 cm, and an overall weight between 300 and 945 grams (Nowak 1999).

Species within this tribe use a wide range of habitats, from woodlands and grasslands, to rocky sites and sandy deserts. Within the genus Xerus, one species, X. inauris, is known to create extensive burrow systems containing one to three social units (Herzig-Straschil 1978), similar to prairie dogs in North America, while another species, X. rutilus, has been observed to prefer a single, isolated burrow system with a primary social unit consisting of a female with her young (O’Shea 1976). Due to extreme temperatures during the mid portion of the day, the ground squirrels are most active in the morning and late evening foraging typically for roots, seeds, fruit, grain, and insects, within the vicinity of their burrow. The burrow is the pivotal site for protection against predators and bearing offspring, and there is no evidence of hibernation or food storage.

In South Africa, it is not uncommon to see these ground squirrels as pets. In some circumstances, they are seen as agricultural pests as a result of feeding on crops of local farmers, and they have been known to carry rabies and the bubonic plague (Nowak 1999).

Characteristics

Most ground squirrels in Xerini exhibit some form of striping in their coats, usually white or black, which is typical among a large group of species within Xerinae. In some species there may be a single stripe along the back, or multiple stripes on each flank of the body, each of which are prominently contrasted by the tan to brownish color of the squirrels’ coat. The tint of their coats is attributed to the soil color of the squirrels’ habitat, where tiny soil particles adhere to the squirrels’ hair and create a coloring effect (Nowak 1999).

Xerus rutilus has an orange tint to its coat because of the deep orange color of the soil its burrow is located in. © 2006

Species in Xerus and Spermophilopsis have uniquely longer claws compared to all other species of squirrels. With an average length of 10 mm, their claws are thick and strong for multi-purpose use (Nowak 1999).

Discussion of Phylogenetic Relationships

A very limited amount of research has been published discussing relationships among the Xerini. The first phylogenetic positions of Xerini ground squirrels within Sciuridae were proposed by Pocock (1923) and Moore (1959). In recent years, Mercer and Roth (2003), and Steppan et al. (2004) have presented some insight into these relationships. As of 2005, the phylogeny of the tribe Xerini stands as three genera, Atlantoxerus, Spermophilopsis, and Xerus, with six distributed species (Wilson and Reeder 2005). No study has included all three genera together.

References

Herzig-Straschil, B. 1978. On the biology of Xerus Inaurius(Zimmerman,1780)(Rodentia, Sciuridae) Z. Saugetierk.43: 262-78.

Mercer, J.M., and V.L. Roth. 2003. The effects of Cenozoic global change on squirrel phylogeny. Science, 1568–1572.

Moore, J.C. 1959. Relationships among the living squirrels of the Sciurinae. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, 159–206.

Nowak, N.M. Walker's Mammals of the World. 6th ed. Vol. 2. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins UP, 1999.

O’Shea, T.J. 1976. Home range, social behavior, and dominance relationships in the African unstriped ground squirrel Xerus Rutilus. J. Mamm. 57: 450-460.

Pocock, R.I. 1923. The classification of the Sciuridae. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London, 209–246.

Steppan, S. J., B. L. Storz, and R. S. Hoffmann. 2004. Nuclear DNA phylogeny of the squirrels (Mammalia: Rodentia) and the evolution of arboreality from c-myc and RAG1. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution.30:703-719.

Wilson, D. E., and D. M. Reeder (Eds.). 2005. Mammal Species of the World, Third Edition. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, MD.

Title Illustrations

| Scientific Name | Xerus |

|---|---|

| Comments | African ground squirrel |

| Creator | Photograph by Gary M. Stolz |

| Specimen Condition | Live Specimen |

| Source Collection | U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Online Digital Media Library |

About This Page

Scott J. Steppan

Florida State University, Tallahassee, Florida, USA

Florida State University, Tallahassee, Florida, USA

Correspondence regarding this page should be directed to Scott J. Steppan at and Shawn M. Hamm at

Page copyright © 2006 Scott J. Steppan and

All Rights Reserved.

- Content changed 10 August 2006

Citing this page:

Steppan, Scott J. and Shawn M. Hamm. 2006. Xerini. African ground squirrels. Version 10 August 2006 (under construction). http://tolweb.org/Xerini/16817/2006.08.10 in The Tree of Life Web Project, http://tolweb.org/

Go to quick links

Go to quick search

Go to navigation for this section of the ToL site

Go to detailed links for the ToL site

Go to quick links

Go to quick search

Go to navigation for this section of the ToL site

Go to detailed links for the ToL site