Haglidae

Ambidextrous and hump-winged crickets

Darryl T. Gwynne and Glenn K. Morris

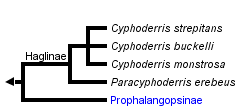

This tree diagram shows the relationships between several groups of organisms.

The root of the current tree connects the organisms featured in this tree to their containing group and the rest of the Tree of Life. The basal branching point in the tree represents the ancestor of the other groups in the tree. This ancestor diversified over time into several descendent subgroups, which are represented as internal nodes and terminal taxa to the right.

You can click on the root to travel down the Tree of Life all the way to the root of all Life, and you can click on the names of descendent subgroups to travel up the Tree of Life all the way to individual species.

For more information on ToL tree formatting, please see Interpreting the Tree or Classification. To learn more about phylogenetic trees, please visit our Phylogenetic Biology pages.

close boxIntroduction

The haglids were very diverse from the late Permian to the early Cretaceous (Sharov 1968; Storozhenko 1997), but only five relict species survive today. These are the short-winged Paracyphoderris erebeus and three species of Cyphoderris (Haglinae) (females are micropterous); and the macropterous Prophalangopsis obscura (F. Walker) (Prophalangopsinae) described from a single male specimen collected in northern India in the mid 1800s (Caudell 1911) (see figure below).

Prophalangopsis obscura (Prophalangopsinae) known only from a single male specimen (from Caudell 1911)

Most of the available biological information on the family is for haglines, particularly Cyphoderris. Both hagline genera inhabit coniferous taiga zones: Cyphoderris is confined to the Rocky mountains of northwestern North America in Colorado - Wyoming (C. strepitans), and Montana, Idaho, Oregon, Washington, British Columbia, and Alberta (C. buckelli and C. monstrosa) (Morris and Gwynne 1978); Paracyphoderris was described from the Sino-russian border north of Manchuria (Storozhenko 1980).

Adult Cyphoderris emerge in spring and are active only at night when the insects move into low bushes or coniferous trees to mate and to feed on vegetation (staminate cones and leaf-galls of sagebrush are known food items). During daylight adults and nymphs of both Cyphoderris and Paracyphoderris retreat into shallow burrows, often under stones. Oviposition behavior is unknown but as female haglines have lost the sword-like ovipositor characteristic of most Ensifera, they probably lay eggs in burrows; the few ensiferans that show maternal care of eggs or young have a reduced or absent ovipositor (Gwynne 1995). Cyphoderris appear to have a two-year life cycle as two distinct age cohorts - adults and half-grown larvae - can be found in spring.

Mating Behavior

Male Cyphoderris call to attract females (Snedden and Irazusta 1994) using musical trills (12 - 13 kHz) while perched in bushes (C. strepitans, the "sagebrush cricket") or high on the trunks of conifers (all three Cyphoderris species). As most of the adult activity is in spring at high elevations, males often call in adverse conditions where snow can be present and the ambient temperature is low (a calling male C. strepitans is the record holder at -8°C (Dodson, Morris, and Gwynne 1983)).

Cyphoderris are known as ambidextrous crickets, because, in contrast to other Ensifera using tegminal stridulation (grylloids and Tettigoniidae), they have a functional file on the underside of each tegmen and will often switch wings during a singing bout (Morris and Gwynne 1978; Spooner 1973). Two functional files are also found in the katydids Neduba (Tettigoniinae) and Megatympanon speculatum (Listroscelidinae) but, in contrast to Cyphoderris, males in these taxa appear to use just one file (Morris and Gwynne 1978).

Mating in Cyphoderris (Dodson, Morris, and Gwynne 1983) begins with the female mounting the male and feeding on his specialized fleshy hind wings. During this meal males hold on to females using a pinching organ on the 8th and 10th tergites (Morris 1979), a "gin trap" that appears to function in holding a female struggling to uncouple from a non-virgin male (Sakaluk et al. 1995). Such female struggling may reflect a preference for virgin males able to supply a full-sized spermatophylax, the meal that is attached to the spermatophore (in nature, there is a mating advantage to virgin male C. strepitans (Morris et al. 1989; Snedden 1996)).

Discussion of Phylogenetic Relationships

The above phylogeny simply follows the classification of the two subfamilies. Haglids share the following characters which appear to be synapomorphies (Kevan 1982; Morris and Gwynne 1978): switch-wing singing using two functional files (see Mating Behavior) with the male tegminal stridulatory apparatus occupying a large diffuse area (not limited to cubitoanal region), three tarsal segments (Haglinae only; Prophalangopsis obscura has four), ovipositor very short (approx. 2 mm) (the female of Prophalangopsis is unknown).

References

Caudell, A.N. 1911. Orthoptera: Fam. Locustidae: Subfam. Prophalangopsine. Genus Prophalangopsis Walker. Genera Insectorum 120:6.

Dodson, G.N., G.K. Morris, and D.T. Gwynne. 1983. Mating behavior of the primitive orthopteran genus Cyphoderris. In Orthopteran Mating Systems: Sexual Competition in a Diverse Group of Insects, ed. by D. T. Gwynne and G. K. Morris, Boulder, Colo., Westview Press. Pp. 305-318.

Gwynne, D. T. 1995. Phylogeny of the Ensifera (Orthoptera): a hypothesis supporting multiple origins of acoustical signalling, complex spermatophores and maternal care in crickets, katydids, and weta. J. Orthop. Res. 4:203-218.

Kevan, D.K. McE. 1982. Orthoptera. In Synopsis and Classification of Living Organisms, ed. by S. P. Parker, New York, McGraw Hill. Pp. 352-383.

Morris, G.K. 1979. Mating systems, paternal investment and aggressive behavior of acoustic orthoptera. Fla. Entomol. 62:9-17.

Morris, G.K., and D.T. Gwynne. 1978. Geographical distribution and biological observations of Cyphoderris (Orthoptera: Haglidae) with a description of a new species. Psyche 85:147-167.

Morris, G.K., D.T. Gwynne, D.E. Klimas, and S.K. Sakaluk. 1989. Virgin male mating advantage in a primitive acoustic insect (Orthoptera: Haglidae). J. Insect Behav. 2:173-185.

Sakaluk, S. K., P. J. Bangert, A.-K. Eggert, C. Gack, and L. V. Swanson. 1995. The gin trap as a device facilitating coercive mating in sagebrush crickets. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 261:65-71.

Sharov, A.G. 1968. Phylogeny of the Orthopteroidea. Trans. Paleontol. Instit. Acad. Sci. 118:1-216.

Snedden, W. A. 1996. Lifetime mating success in male sagebrush crickets : sexual selection constrained by a virgin male mating advantage. Anim. Behav. 51:1119-1125.

Snedden, W.A., and S. Irazusta. 1994. Attraction of female sagebrush crickets to male song: the importance of field bioassays. J. Insect Behav. 7:233-236.

Spooner, J.D. 1973. Sound production in Cyphoderris monstrosa (Orthoptera: Prophalangopsidae). Ann. Ent. Soc. Amer.:4-5.

Storozhenko, S.V. 1997. Fossil history and phylogeny of orthopteroid insects. In The Bionomics of Grasshoppers, Katydids and their Kin, ed. by S. K. Gangwere, M. C. Muralirangan and M. Muralirangan, Wallingford, U.K., CAB International. Pp. 59-82.

Storozhenko, S.Y. 1980. Haglidae (Orthoptera) - a new family for the USSR fauna. Rev. d'Entomol. de l'URSS 59:114-117.

Title Illustrations

| Scientific Name | Cyphoderris strepitans (Haglinae) |

|---|---|

| Comments | Sagebrush cricket |

| Specimen Condition | Live Specimen |

| Sex | Male |

| Copyright |

© Darryl T. Gwynne

|

| Scientific Name | Cyphoderris strepitans (Haglinae) |

|---|---|

| Comments | Sagebrush cricket |

| Specimen Condition | Live Specimen |

| Sex | Female |

| Copyright |

© Darryl T. Gwynne

|

About This Page

Darryl T. Gwynne

University of Toronto, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada

Glenn K. Morris

University of Toronto, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada

Page copyright © 2002

All Rights Reserved.

- First online 18 October 2002

Citing this page:

Gwynne, Darryl T. and Glenn K. Morris. 2002. Haglidae. Ambidextrous and hump-winged crickets. Version 18 October 2002. http://tolweb.org/Haglidae/13297/2002.10.18 in The Tree of Life Web Project, http://tolweb.org/

Go to quick links

Go to quick search

Go to navigation for this section of the ToL site

Go to detailed links for the ToL site

Go to quick links

Go to quick search

Go to navigation for this section of the ToL site

Go to detailed links for the ToL site