Collomia

Leigh Johnson

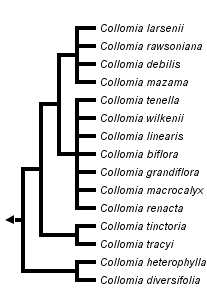

This tree diagram shows the relationships between several groups of organisms.

The root of the current tree connects the organisms featured in this tree to their containing group and the rest of the Tree of Life. The basal branching point in the tree represents the ancestor of the other groups in the tree. This ancestor diversified over time into several descendent subgroups, which are represented as internal nodes and terminal taxa to the right.

You can click on the root to travel down the Tree of Life all the way to the root of all Life, and you can click on the names of descendent subgroups to travel up the Tree of Life all the way to individual species.

For more information on ToL tree formatting, please see Interpreting the Tree or Classification. To learn more about phylogenetic trees, please visit our Phylogenetic Biology pages.

close boxIntroduction

Collomia, sometimes called "mountain trumpets", has 15 species. The genus derives its name from the greek word "Kolla", which means "gluton", in reference to the sticky nature of the seeds when wet. Thomas Nuttall named the genus in 1818 based on a plant he collected in 1811 near the junction of the Cheyenne and Missouri Rivers (in present day South Dakota, U.S.A.). The first species belonging to this genus to be named, however, was collected in the late 1700's in Chile, and was considered a member of the genus Phlox. Collomia species vary from obscure to showy; all 15 species share a distinct odor that, while not offensive, isn't really attractive either.

Characteristics

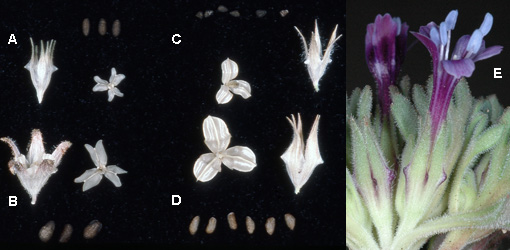

Calyces and fruits of Collomia species showing the pitcher-like projections on the calyx and the reflexed fruit walls from the explosively dehiscent fruit. A = C. linearis; B = C. grandiflora; C = C. heterophylla; D = C. diversifolia; E = C. larsenii. © 2008

Collomia are easily distinguished from all other members of the Phlox family by their calyx (sepals)—the outermost part of each flower that is typically green. The five sepals are fused about half of their length into a tube; the portion of the sepals that are not fused (lobes) are more or less triangular with the exact shape and proportions being important for identifying some species. Where adjacent lobes meet (the sinus), a projection somewhat like the spout of a pitcher used to serve water is formed, and it is this projection that distinguishes Collomia calyces from other Polemoniaceae. Many descriptions of Collomia describe the calyx as being entirely herbaceous (leaf-like), but each sepal is really fused to the next by a narrow membrane and it is this membrane that forms the pitcher-like projection between each lobe (in many other Polemoniaceae, the membrane is considerably more obvious). Collomia also have eight pairs of chromosomes (compared to nine in most Polemoniaceae, including all Gilieae with some exceptions in Allophyllum), and the capsule "explodes" at maturity to disperse its seeds short distances. Other general features, such as having flowers clustered into small to large heads, seeds that are sticky when wet, and having just three seeds per fruit, are not unique to Collomia and not even true for all of the 15 species.

Geographic Distribution and Habitat

Collomia are entirely New World species with a center of diversity in the Western United States. Whereas Collomia biflora is found only in southern South America and Collomia linearis ranges east of the Mississippi River in the United States, the remaining species are found natively only west of the Rocky Mountains, generally at higher latitudes and elevations. Collomia grandiflora has escaped from cultivation on several continents with persistent populations reported in Argentina, Australia, and Europe. In general, Collomia are montane species that, while not weedy, often occur in disturbed sites such as along forest roads and trails. About half of the species have large geographic ranges while the other half are restricted to either narrow geographic regions, narrow ecological zones and soil types, or both.

Horticulture

Collomia are not well known horticulturally. The duration of bloom is brief for all species, and the annual species are mostly too small-flowered and uninteresting vegetatively to gain commercial appeal. The red flowers of Collomia biflora and the larger salmon flowers of Collomia grandiflora have brought these species into limited cultivation by enthusiasts, and seeds are generally available. 'Neon,' a cultivar of C. biflora, was introduced in 1983 under the species name "Collomia coccinea," a name synonymous with C. biflora that persists in the horticultural trade. The perennial species are all very showy, but also have more difficult cultural requirements and may be very short lived. The alpine species Collomia debilis is sometimes available as a rock garden plant. Given the restricted distributions of the perennial species, gardeners should refrain from removing plants from the wild.

Ethnobotany

Known ethnobotanical use of Collomia is restricted to the two most common species. The Okanagan-Colville peoples used Collomia grandiflora roots for high fevers, while both roots, leaves, and stems were taken as a laxative; the Paiutes used the leaves of this species as a protective covering for filled berry containers. The Gosiutes applied a poultice of Collomia linearis to wounds and bruises.

Scientific Interest

Collomia has been most thoroughly studied botanically in two areas. First, the seeds have been studied with SEM (scanning electron microscopy) and TEM (transmission electron microscopy) to better understand the basis for the sticky covering that is produced when the dry seeds contact water. Rather than simply producing a mucilage or pectin substance, coiled secondary wall material within the outermost layer of the seed coat expands and pushes out of each cell as a helical or spring-like thread (Schnepf and Deichgraeber, 1983).

Second, Collomia grandiflora is the only documented member of the Phlox family with cliestogamy (closed flowers). In this species, the corolla (petals) can be "normal" and showy, typically over 1.5 cm in length and open for insect pollination. They can also, however, be obscure (4 mm or less), closed, and self pollinated. A single plant can have all open flowers, all closed flowers, or a combination of both, and C. grandiflora served as an important model for studying this mixed reproductive system (e.g., Wilken, 1982; Minter and Lord, 1983; Ellstrand et al., 1984; Lord and Eckard, 1984; Lord et al., 1989).

Discussion of Phylogenetic Relationships

The first hypothesis of phylogenetic relationships in Collomia was proposed by Wherry (1944) who suggested the perennial species were ancestral and the linear leaved annuals the most advanced. Wherry grouped species into three sections that have been accepted by latter authors (e.g., Grant 1959; Chuang et al. 1978; Hsiao and Chuang 1981). Section Collomiastrum contained the four perennial species, section Courtoisa contained the two species that have more than three seeds per fruit, and the remaining species were placed in section Collomia.

With no basis beyond emphasizing the perennial habit at the expense of the many similarities that unite Collomia as monophyletic, Welsh (2000) elevated section Collomiastrum to the rank of genus and placed the single perennial species found in Utah into this new genus. This taxonomic change is not supported phylogenetically. The perennial species are derived within the genus, rather than being sister to the remaining species in the genus.

Grant (1959) accepted Wherry's views of relationships and suggested several progenitor/derivative species pairs. In this view, new species have arisen most likely from allopatric speciation. Hybridization, which has been shown to be important in other Polemoniaceae genera such as Gilia and Phlox, was never considered important in the history of Collomia, but now appears to be just as important as divergent speciation. Comparative DNA sequencing provides strong evidence that two Collomia species, C. biflora and C. wilkenii, are allotetraploids (Johnson and Johnson, 2006). Allotetraploids are formed when two diploid species hybridize and the offspring has twice as many chromosomes as its parents. Collomia mazama has most likely obtained its chloroplast from an annual species and C. diversifolia has also likely experienced hybridization in its past.

Collomia diversifolia and C. heterophylla are strongly supported as sister species by chloroplast DNA, but not with nuclear rDNA ITS or low copy nuclear genes. C. diversifolia's pollen morphology matches the linear leaved annuals such as C. linearis (Chuang et al. 1978), but it is otherwise similar to C. heterophylla in habit and in its number of seeds per fruit.

Collomia tracyi and C. tinctoria are strongly supported as sister taxa morphologically and with DNA sequence data. They have a unique pollen type in the genus and do not belong phylogenetically with the other species of section Collomia.

The perennial species are well-supported as monophyletic with nuclear DNA sequences and morphology (e.g., Chuang et al., 1978; Hsaio and Chuang, 1981), but C. mazama possesses a chloroplast genome that appears sister to the large group of linear leaved annuals.

The linear leaved annuals excluding Collomia grandiflora form a group, with C. grandiflora either sister or unresolved in its relationship in the genus. Chuang et al. (1978) suggested the pollen of C. grandiflora was somewhat intermediate between the other linear leaved species and the perennial species.

References

Chuang, T., W. C. Hsieh and D. H. Wilken. 1978. Contribution of pollen morphology to systematics of Collomia (Polemoniaceae). American Journal of Botany. 4:450-458.

Ellstrand, N. C., E. M. Lord and K. J. Eckard. 1984. The inflorescence as a metapopulation of flowers: position-dependent differences in function and form in the cleistogamous species Collomia grandiflora Dougl. Ex Lindl. (Polemoniaceae). Botanical Gazette 3:329-333.

Hsaio, Y. and T. Chuang. 1981. Seed-coat morphology and anatomy in Collomia (Polemoniaceae). American Journal of Botany 9:1155-1164.

Johnson, L. A. and R. L. Johnson. 2006. Morphological delimitation and molecular evidence for allopolyploidy in Collomia wilkenii (Polemoniaceae), a new species from northern Nevada. Systematic Botany. 2:349-360.

Lord, E. M. and K. J. Eckard. 1984. Incompatibility between the dimorphic flowers of Collomia grandiflora, a cleistogamous species. Science 223:695-696.

Lord, E. M., K. J. Eckard, and W. Crone. 1989. Development of the dimorphic anthers in Collomia grandiflora: evidence for heterochrony in the evolution of the cleistogamous anther. Journal of Evolutionary Biology 2:81-94.

Minter, T. C. and E. M. Lord. 1983. A comparison of cleistogamous and chasmogamous floral development in Collomia grandiflora Dougl. Ex Lindl. (Polemoniaceae). American Journal of Botany. 10:1499-1508.

Puntieri, J. G. and C. A. M. Brion. 2005. Nuevas citas para la flora Argentina: Collomia grandiflora (Polemoniaceae) y Potentilla recta (Rosaceae). Hickenia 3: 227-258.

Schnepf, E. and G. Deichgraeber. 1983. Structure and formation of fibrillar mucilages in seed epidermis cells: 1. Collomia grandiflora (Polemoniaceae).

Wherry, E. T. 1944. Review of the genera Collomia and Gymnosteris. American Midland Naturalist. 1:216-231.

Wilken, D. H. 1977. Local differentiation for phenotypic plasticity in the annual Collomia linearis (Polemoniaceae). Systematic Botany. 2:99-108.

Wilken, D. H. 1978. Vegetative and floral relationships among western North American populations of Collomia linearis Nuttall (Polemoniaceae). American Journal of Botany. 8:896-901.

Wilken, D. H. 1982. The balance between chasmogamy and cleistogamy in Collomia grandiflora (Polemoniaceae). American Journal of Botany. 8:1326-1333.

Information on the Internet

- Ethnobotanical uses for Collomia. University of Michigan, Native American Ethnobotany site.

Title Illustrations

| Scientific Name | Collomia linearis |

|---|---|

| Location | near Holden, UT, USA |

| Specimen Condition | Live Specimen |

| Identified By | Leigh Johnson |

| Sex | Perfect flowers |

| Size | ca. 8-10 inches tall |

| Copyright | © 2005 |

| Scientific Name | Collomia debilis |

|---|---|

| Location | Mt. Loafer, UT |

| Specimen Condition | Live Specimen |

| Identified By | Leigh Johnson |

| Sex | Perfect flowers |

| Image Use |

This media file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial License - Version 3.0. This media file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial License - Version 3.0.

|

| Copyright |

© 2000

|

About This Page

The development of this page was supported by NSF award DEB 0344873 to Leigh Johnson; Lisa Glazier contributed to the construction of this page through a BYU undergraduate ORCA award.

Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah, USA

Correspondence regarding this page should be directed to Leigh Johnson at

Page copyright © 2008

Page: Tree of Life

Collomia.

Authored by

Leigh Johnson.

The TEXT of this page is licensed under the

Creative Commons Attribution License - Version 3.0. Note that images and other media

featured on this page are each governed by their own license, and they may or may not be available

for reuse. Click on an image or a media link to access the media data window, which provides the

relevant licensing information. For the general terms and conditions of ToL material reuse and

redistribution, please see the Tree of Life Copyright

Policies.

Page: Tree of Life

Collomia.

Authored by

Leigh Johnson.

The TEXT of this page is licensed under the

Creative Commons Attribution License - Version 3.0. Note that images and other media

featured on this page are each governed by their own license, and they may or may not be available

for reuse. Click on an image or a media link to access the media data window, which provides the

relevant licensing information. For the general terms and conditions of ToL material reuse and

redistribution, please see the Tree of Life Copyright

Policies.

- First online 29 December 2008

- Content changed 29 December 2008

Citing this page:

Johnson, Leigh. 2008. Collomia. Version 29 December 2008 (under construction). http://tolweb.org/Collomia/22995/2008.12.29 in The Tree of Life Web Project, http://tolweb.org/

Go to quick links

Go to quick search

Go to navigation for this section of the ToL site

Go to detailed links for the ToL site

Go to quick links

Go to quick search

Go to navigation for this section of the ToL site

Go to detailed links for the ToL site