Ankylosauridae

Kenneth Carpenter

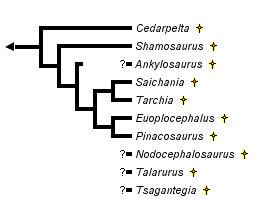

This tree diagram shows the relationships between several groups of organisms.

The root of the current tree connects the organisms featured in this tree to their containing group and the rest of the Tree of Life. The basal branching point in the tree represents the ancestor of the other groups in the tree. This ancestor diversified over time into several descendent subgroups, which are represented as internal nodes and terminal taxa to the right.

You can click on the root to travel down the Tree of Life all the way to the root of all Life, and you can click on the names of descendent subgroups to travel up the Tree of Life all the way to individual species.

For more information on ToL tree formatting, please see Interpreting the Tree or Classification. To learn more about phylogenetic trees, please visit our Phylogenetic Biology pages.

close boxIntroduction

The Ankylosauridae, or ankylosaurids, are the stereotypical armor dinosaurs having a large club of bone on the end of the tail. The body is encased in armor plates like the nodosaurids', but long spines on the neck and shoulder are not present. In some species, however, there are tall, thin-walled cones located on the back and shoulder that superficially resemble spines. Ankylosaurus, the name best known by non-paleontologists, is actually very poorly known scientifically. Only three specimens have been found and only one of these, the holotype, has been described in any detail (Brown, 1908). Perhaps the best known scientifically is Euoplocephalus because it is known from several specimens, including at least two that have armor preserved in life position (Nopcsa, 1928). This has allowed accurate life-reconstructions (e.g., Carpenter, 1982, 1997).

Figure 1. Skeleton of Euoplocephalus, the best known ankylosaurid from the Late Cretaceous of North America. Characteristic features of the ankylosaurids include the tail club and two rows of neck armor.

The earliest ankylosaurid is Cedarpelta from the Lower Cretaceous (Albian) of Utah (Carpenter et al., 2001). The taxon is represented by two partial skulls and skeletons having an estimated skull length of 60 cm. One skull is mostly disarticulated, allowing the individual bones of an ankylosaur to be described in multiple view for the first time. The skull shows some similarities with Shamosaurus from the Lower Cretaceous of Mongolia, especially in its boxy appearance.

Ankylosaurids diversified during the Campanian (83.5-71.5 mya), but only in Asia and North America. What prevented their migration to South America is puzzling considering that nodosaurids were not hindered. Apparently the ecological requirements of nodosaurids and ankylosaurids were different enough to form a barrier to ankylosaurids but not to nodosaurids. Such an interpretation is complicated by the apparent extinction of the ankylosaurids in North America at about the same time as the extinction of the nodosaurids (i.e., pre-asteroid impact). If true, this would imply that ankylosaurids were also affected by the loss of habitat during the regression of the Cretaceous Seaway. As for the Asian ankylosaurids, the end of the Cretaceous extinction of all dinosaurs is too poorly documented to know when ankylosaurid extinction occurred.

Characteristics

Ankylosaurids characteristically have a skull width that is 3/4 or more its length, and in top view, the skull is typically triangular. The premaxillary beak is longer than wide in primitive forms (e.g., Cedarpelta from Utah, Carpenter et al., 2001) and very wide (often wider than long) in advanced forms (e.g., Euoplocephalus). The wide beak suggests that ankylosaurids were not selective feeders, but grazed on low vegetation much like the hippo does today. The teeth of ankylosaurids are tiny compared to skull size, and advanced species have a swollen crown base. The lateral temporal fenestra is closed, apparently by the rearward expansion of the postorbital based on a disarticulated skull of Cedarpelta from Utah (Carpenter, et al., 2001). On the lower jaw, the coronoid process is low as in polacanthids, rather than tall as in nodosaurids.

Figure 2. Skull of Tarchia in side (left) and top (right) views. The characteristic features of the skull include: skull as wide or wider than long, large jugal and postorbital "horns" and numerous small scale impressions (ornamentation) onto the skull surface.

The skull surface is typically covered with small sculpturing (except in Saichania and Nodocephalosaurus), while large, pyramid-shaped "horns" occur at the rear corners of the skull. The sculpturing reflects the scales that once covered the skull. A grow series of Pinacosaurus and Cedarpelta from Utah show that sculpturing of the skull surface is ontogenetically controlled (Carpenter 2001), with the sculpturing more prominent in older individuals.

Figure 3. Shoulder girdle of Euoplocephalus showing the position of the acromion along the top edge of the scapula.

The scapula, or shoulder blade, is not as distinctive in ankylosaurids as it is in nodosaurids or polacanthids because the acromion process remains along the dorsal edge. The scapula of Pinacosaurus is remarkable for its slenderness, but no general trend can be seen in this direction among other advanced ankylosaurids. The deltopectoral crest does not project forwards as much as it does in polacanthids and nodosaurids. Furthermore. the distal condyles of the humerus are in nearly the same vertical plane as the deltopectoral crest. The forth trochanter of the femur is located distal to the mid-point. The fore- and hindfeet are not known for all ankylosaurid species. In general, the hind feet, or pes, of advanced ankylosaurids (e.g., Euoplocephalus) have only three toes, whereas primitive ones (e.g. Talarurus) have four.

Figure 4. Skeleton of Talarurus, an ankylosaur from the Upper Cretaceous of Mongolia. Note the long, low body and tail club, which is quite slender in this species.

Body armor consists mostly of thin-walled scutes. Some of these are large cones that were arranged in parallel rows on the back (e.g., Euoplocephalus). Other ankylosaurids had low cones and broad plates arranged into narrow bands (e.g., Talarurus). The most distinguishing feature about ankylosaurids is the bone tail club (Coombs, 1978). The club is actually composed of at least two very large bone plates and several smaller plates that are partially or completely fused together. These plates surround fused distal vertebrae that form a rigid "handle" to the club. Typically, the last half of the tail is fused together. Ossified tendons, much like those found in the drumstick of a turkey, also envelop the vertebrae providing additional strength.

Discussion of Phylogenetic Relationships

Phylogenetic research in ankylosaurids is complicated by the incompleteness of most specimens. The best known taxa are represented by several specimens representing the entire skeleton (e.g., Saichania, Pinacosaurus, Euoplocephalus; Maryanska, 1977; Carpenter, 1982). Most other taxa are only known from skulls (e.g., Tsagantegia) making analysis difficult.

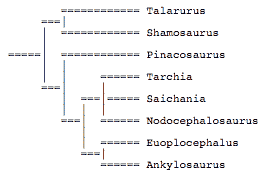

Coombs and Maryanska (1990) have proposed the following relationships among ankylosaurids:

This analysis was flawed due to the use of certain characters, such as orbits facing more laterally, which are actually plesiomorphic for the group.

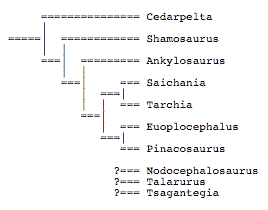

Sullivan (1999) has presented an alternative phylogenetic tree based only on cranial characters:

A more inclusive phyletic analysis presented in detail elsewhere (Carpenter 2001), differs considerably from that of Coombs and Maryanska (1990) and Sullivan (1999):

There are some similarities between this tree and that given by Sullivan, notably in the pairing of Saichania and Tarchia and the relative placement higher on the tree of Euoplocephalus relative to the Saichania-Tarchia pair. The placement of Ankylosaurus so low on the tree is tentative pending a restudy of that genus now under way.

Paleobiology

Ankylosaurids are known from the Lower and Upper Cretaceous of North America and Asia. Many of the Asian localities are in sediments indicative of semiarid and arid environments, including sand dunes (e.g., Djadokhta Formation). In contrast, most of the North American localities are in sediments deposited in the wet coastal plain environments (e.g., Dinosaur Park Formation, Hell Creek Formation), although some sediments indicate deposition in seasonal environments (Cedar Mountain Formation). Thus, ankylosaurids had a broader environmental range than did the nodosaurids or polacanthids.

The diet of ankylosaurids is generally thought to be vegetation, although Nopcsa (1928) suggested that they were insectivorous. It is difficult to image how a 5 ton animal could find enough insects to sustains itself. However, a herbivorous diet for an elephantine-sized animal is more feasible. The muzzle of ankylosaurids is typically wide, in a manner analogous to a hippopotamus, suggesting that ankylosaurids were also non-selective grazers. The cheek teeth are swollen, and show wear indicative of complex chewing, especially Euoplocephalus (Rybczynski and Vickaryous, 2001).

The armor of ankylosaurs consists of two bands of large plates on the neck and thin-walled scutes arranged in rows across the back and tail. This armor is supplemented in Saichania and Euoplocephalus by tall conical scutes on the back. The most characteristic armor of ankylosaurids is, of course, the tail club. It varies considerably in shape among the different genera and even among individuals of the same species. The club is most likely an offensive weapon to deter predators, but a display function is possible as well. Perhaps waving the club was a form of agonistic display against others of its kind

References

Brown, B. 1908. The Ankylosauridae, a new family of armored dinosaurs from the Upper Cretaceous. American Museum of Natural History Bulletin 24:187-201.

Carpenter, K. 1982. Skeletal and dermal armor reconstruction of Euoplocephalus tutus (Ornithischia: Ankylosauridae) from the Late Cretaceous Oldman Formation of Alberta. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences, 19:689-697.

Carpenter, K. 1997. Ankylosaurs. Pp. 308-316 in J. Farlow and M. Brett-Surman (eds.), The Complete Dinosaur. Indiana University Press, Bloomington.

Carpenter, K. 2001. Phylogenetic Analysis of the Ankylosauria. Pp. 455-483 in K. Carpenter (ed.). The Armored Dinosaurs. Indiana University Press, Bloomington.

Carpenter, K., J.I. Kirkland, D. Burge and J. Bird. 2001. Disarticulated Skull of a New Primitive Ankylosaurid From the Lower Cretaceous of Eastern Utah. Pp. 211-238 in K. Carpenter (ed.). The Armored Dinosaurs. Indiana University Press, Bloomington.

Coombs, W. 1978. The families of the ornithischian dinosaur order Ankylosauria. Journal of Paleontology, 21:143-170.

Coombs, W., and T. Maryanska. 1990. Ankylosauria. Pp. 456-483 in D. Weishampel, P. Dodson and H. Osmolska (eds.), The Dinosauria. University of California Press, Berkeley.

Maryanska, T., 1977. Ankylosauridae (Dinosauria) from Mongolia. Palaeontologia Polonica 37:85-151.

Nopcsa, F. 1928. Palaeontological notes on reptiles. Geologica Hungerica, Seria Palaeontologica 1:1-84.

Rybczynski, N. and M.K. Vickaryous. 2001. Evidence of Complex Jaw Movement in the Late Cretaceous Ankylosaurid, Euoplocephalus tutus (Dinosauria: Thyreophora). Pp. 299-317 in K. Carpenter (ed.). The Armored Dinosaurs. Indiana University Press, Bloomington.

Sullivan, R.M. 1999. Nodocephalosaurus kirtlandensis, gen. et sp. nov., a new ankylosaurid dinosaur (Ornithischia: Ankylosauria) from the Upper Cretaceous Kirtland Formation (upper Campanian), San Juan Basin, New Mexico. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 19: 126-139.

About This Page

Thanks to Katja Schulz, The Tree of Life Project, for her asistance in getting these pages designed and online, and to Brian Franczak for permission to use the image of Euoplocephalus.

All other illustrations are by the author, copyright © 2000, Kenneth Carpenter.

Denver Museum of Natural History, Denver, Colorado, USA

Page copyright © 2000

Page: Tree of Life

Ankylosauridae.

Authored by

Kenneth Carpenter.

The TEXT of this page is licensed under the

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial License - Version 3.0. Note that images and other media

featured on this page are each governed by their own license, and they may or may not be available

for reuse. Click on an image or a media link to access the media data window, which provides the

relevant licensing information. For the general terms and conditions of ToL material reuse and

redistribution, please see the Tree of Life Copyright

Policies.

Page: Tree of Life

Ankylosauridae.

Authored by

Kenneth Carpenter.

The TEXT of this page is licensed under the

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial License - Version 3.0. Note that images and other media

featured on this page are each governed by their own license, and they may or may not be available

for reuse. Click on an image or a media link to access the media data window, which provides the

relevant licensing information. For the general terms and conditions of ToL material reuse and

redistribution, please see the Tree of Life Copyright

Policies.

- First online 22 December 2000

- Content changed 10 January 2002

Citing this page:

Carpenter, Kenneth. 2002. Ankylosauridae. Version 10 January 2002 (under construction). http://tolweb.org/Ankylosauridae/15775/2002.01.10 in The Tree of Life Web Project, http://tolweb.org/

Go to quick links

Go to quick search

Go to navigation for this section of the ToL site

Go to detailed links for the ToL site

Go to quick links

Go to quick search

Go to navigation for this section of the ToL site

Go to detailed links for the ToL site